The single most recognisable feature of the landscape of central Warsaw is the Palace of Culture and Science (Palac Kultury i Nauki). An enormous building that both dominates the skyline and creates a kind of urban spatial vacuum, as anyone who has tried to traverse the confusing hodgepodge of parks, markets, staircases and carparks that encircle the building will attest. It is a site that I find myself simultaneously repelled by and attracted to, returning time and time again to bask in its dehumanising and overbearing grandeur.

The Palace conceived as a non-returnable gift to the Polish people by Joseph Stalin in 1947 was opened in a flurry of state-sponsored pomp in 1955. It is exceptional both in its scale and ostentatious inappropriateness for a city struggling to rebuild itself following the utter decimation wrought upon it by Germany during World War II. Designed and built entirely by Russian architects and labour the building stands as symbol of the dictatorial relationship that existed between the Soviet state and Poland during the post war years. Today it houses a collection of theatres, museums, cinemas, conference halls and sporting facilities, a valuable part of the cultural infrastructure of the city.

Recalling nothing so much as the classic skyscraper (think Empire State Building) in its stepped and spired form the building inverts such modernist allusions by the deployment of an overabundance of classical and folk-art inspired ornamentation. Built in the prevailing Socialist Realist aesthetic of the time the Palace stands apart from contemporaneous developments such as the MDM district of Warsaw that employed a more austere and organically Polish version of the largely vilified style. A style, that following the death of Stalin in 1956 was largely abandoned for more consciously modernist forms.

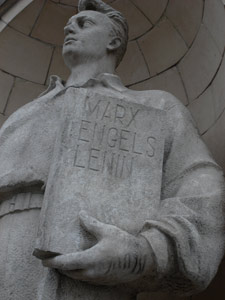

Central to the underlying ideology that informed Socialist Realism was an ideal of self-improvement through “culture”. As if to drive the point home a series of oversized classical sculptures adorn the ground level façade of the Palace depicting among other pursuits drama, music and literature. Of course, at a time of strict state-controlled censorship, there was no recourse made by these lumpen figures to the actual content of such cultural pursuits. The exception to this being a sculpture of a soberly dressed male worker clutching a book inscribed with the names Marx, Engels and Lenin. Beneath the last name a blank space. Originally this space held the name Stalin, but in the “thaw” that begun in 1957 in the wake of his death this detail was removed. One can just about make out the outlines of the letters, a ghostly absence that resonates through the architecture. Like in the building itself Stalin’s presence is felt through its very absence.